In Anbetracht der wachsenden Gefahr der Radikalisierung und des ‘home-grown terrorism’ hat die Bundesregierung in dieser Legislaturperiode die Gelder für das nationale Präventionsprogramm verdreifacht (BMFSFJ, 2017). Die Architektur der Extremismusprävention sowie die Förderung der Demokratie sollen proaktiv weiterentwickelt und verstärkt werden. Laut des Berichtes der Bundesregierung über Arbeit und Wirksamkeit der Bundesprogramme zur Extremismusprävention (2017) stellt besonders die islamistische Radikalisierung innerhalb Deutschlands eine neue Herausforderung dar, der begegnet werden muss. Für dieses Präventionsprogramm werden 2018 100 Millionen Euro in den Eckwerten des Bundeshaushaltes bereitgestellt, die besonders für die Einbindung der Moscheengemeinde, der Prävention im Netz sowie in Schulen, Kitas und Universitäten verwendet werden sollen.

Die komplexe Dynamik dieser verschiedenen Ansätze berechtigt die Frage, wie der Radikalisierung von insbesondere jungen Menschen innerhalb Deutschlands am besten begegnet werden soll, welche Maßnahmen vielversprechend erscheinen – und welche nicht. Wertvolle Erkenntnisse kann das Bundesinnenministerium möglicherweise aus den Erfolgen und Misserfolgen anderer Länder ziehen, wie zum Beispiel aus den Konsequenzen der CONTEST Strategie Großbrittanniens. Ein bedeutsamer Teil der britischen ‘Counter-Terrorism’ Strategie ist der präventive Ansatz ‘Prevent’, der seit 2015 von einer gesetzlichen Verpflichtung ergänzt wird: der umstrittenen ‘Prevent Duty’. Hierbei sind lokale Institutionen (z.B. Schulen) verpflichtet Jugendliche und Kinder zu melden, wenn Anlass zur Vermutung besteht, dass sie erste Zeichen der Radikalisierung aufweisen. Gemäß dieser gesetzlichen Pflicht sind z.B. Lehrer beauftragt, ihre Schüler zu melden – was in der Praxis häufig aufgrund spezifischer Aussagen, Denkweisen oder gar aufgrund des Erscheinungsbildes geschieht. Nicht nur die Indikatoren der Radikalisierung sind umstritten (schließlich handelt es sich hierbei um Jugendliche), sondern auch die möglichen Auswirkungen auf die Meinungsfreiheit innerhalb von Schulen und anderen Bildungsstätten.

Des Weiteren besteht die Gefahr, dass die Prevent Duty kontraproduktive Effekte erzielt: durch einen hauptsächlichen Fokus auf britische Muslime könnten sich diese im Alltag zunehmend stigmatisiert fühlen. Basierend auf sogenannten Freedom of Information requests (FOI) erschließt die folgende kritische Analyse der Prevent Duty, dass ein Großteil der gemeldeten Schüler in der Tat britische Muslime sind.

Der Beitrag ist ursprünglich erschienen im Journal for Deradicalization (Spring 2018), Nr. 14, S. 153-191.

Resisting Radicalisation: A Critical Analysis of the UK Prevent Duty

Abstract

In response to the threat of terrorism and radicalisation, the UK government introduced the counterterrorism strategy CONTEST and its four strands ‘Prepare, Prevent, Protect, Pursue’. As one of these four strands, the ‘Prevent’ strategy dates back to 2003 and is tailored to avert radicalisation in its earliest stages. What stands out as particularly controversial is the statutory duty introduced in 2015 that requires ‘specified authorities’ to “have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism” (Home Office, 2015a, s. 26).

Based on a critical analysis of the so-called Prevent Duty in educational institutions (excluding higher education), I argue that it not only has the potential to undermine ‘inclusive’ safe spaces in schools but may also hold the danger of further alienating the British Muslim population. Certain terminology such as ‘safeguarding’ students who are ‘vulnerable’ to extremist ideas is misleading and conveniently inflated in order to legitimise the Prevent Duty and facilitate its smooth implementation. Largely based on Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, this in-depth analysis is best utilised in combination with empirical research on the impact of Prevent as conducted by Busher et al. (2017).

However, the disproportionate targeting of British Muslims intertwined with the dual role of students as both at risk and, simultaneously, a risk, reveals that the Prevent Duty in educational institutions is deeply flawed in its implementation and has significant potential to alienate and radicalise the British Muslim population.

Introduction

As a result of the rise in international terrorism and traumatic attacks such as the 2004 Madrid and the 2005 London bombings, the subject of Islamic radicalism is at the centre of international and national political debate. Responding to the threat of terrorism and radicalisation, the UK government introduced the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 (Home Office, 2015a). The question of how to address radicalisation is more relevant than ever in the aftermath of contemporary attacks such as Paris in 2015, Brussels in 2016, and the more recent attacks on Westminster, London (March 2017), Manchester (May 2017), the London Bridge and the Borough Market (June 2017) as well as on the Finsbury Park mosque (June 2017). The London terror attack in 2005, now known as 7/7, first highlighted the need to develop specifically tailored counter-terrorism strategies: contrary to 9/11, terrorist attacks in the UK were not perpetrated by individuals entering the UK from the outside but by those who had grown up in the UK – a phenomenon responsible for coining the term ‘homegrown terrorism’ (Abbas, 2007; Cole, 2009; Thomas, 2009). This unanticipated trend has triggered an urgent and on-going debate on how to sufficiently tackle – and potentially prevent – the radicalisation of young people and specifically young British Muslims at an early stage.

As one of the four strands of the government’s counter-terrorism strategy CONTEST, the ‘Prevent’ strategy dates back to 2003 and is specifically tailored “to stop people becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism” (Home Office, 2011a: 9). Since 2003, it has been revised multiple times and is also intended to “work with a wide range of sectors (including education, criminal justice, faith, charities, the internet and health) where there are risks of radicalisation which we need to address” (Home Office, 2011a: 10). Of particular interest is the recently introduced ‘Prevent Duty’. With section 26 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, the government of England and Wales places a ‘statutory duty’ on ‘specified authorities’ to have “due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism” (Home Office, 2015). These specified authorities include the schools of England and Wales. Being viewed as vulnerable teenagers with “young minds already susceptible to feelings of frustration, anger [and] hate” (Abbas, 2007: 4), Muslim youths find themselves at the very core of the national and local debate about ‘Islamist extremism’.

A particular focus on Muslims in combination with the Prevent Duty imposed on educational institutions brings with it a variety of intertwined issues which should be subject to in-depth investigation. These theoretical issues with practical implications can be narrowed down to two main concerns: first, the official presentation of Prevent as a strategy providing a ‘safe space’ (Ramsay, 2017) call into question whether the statutory duty – in practice – creates or rather undermines safe spaces for students and subsequently facilitates a chilling effect on human rights such as the freedom of expression.

A Brief History of the Prevent Strategy

As one of four strands (Pursue, Prevent, Protect and Prepare) of the UK government’s counterterrorism strategy Contest, Prevent was originally introduced in 2003 and defines an ongoing struggle and “effort to find a legitimate democratic response to terrorism” (Cole, 2009: 138). Essentially, the Prevent strategy aims at preventing the radicalisation of individuals – based on the assumption that “terrorists were individuals who has been through a process of radicalization” (Edwards, 2016: 298). Due to allegations of failure to confront the extremist ideology at the heart of the threat” and misplaced funding (Home Office, 2011b), the Prevent strategy was revised in 2011 under the Coalition Government to achieve a clearer separation of “community based integration work from the more direct counter-terrorism activities” (Dawson and Pepin, 2017: 3). Three primary objectives are formulated in the Prevent strategy:

- respond to the ideological challenge of terrorism and the threat we face from those who promote it;

- prevent people from being drawn into terrorism and ensure that they are given appropriate advice and support; and

- work with sectors and institutions where there are risks of radicalisation which we need to address (Home Office, 2011b: 7).

It is evident that the challenge of tackling terrorism is perceived as primarily related to ideology. Furthermore, in the 2011 revised Prevent strategy, the second objective (preventing people from being drawn into terrorism) is inextricably tied to the notion of vulnerability. Identifying radicalisation as an ongoing process, Prevent aims to intercept this process, to support vulnerable people and to thereby prevent them from being drawn into “terrorism-related activity (Home Office, 2011b: 8). The delivery and implementation of Prevent is coordinated by the Office for Security and Counterterrorism branch (OSCT) in the Home Office. Characterised by a predominantly local approach, the enforcement of Prevent relies on local governments and community engagement. These local authorities include “youth offending services; social workers; housing and voluntary groups” as well as educational institutions and health services (Home Office, 2011: 56). According to the Home Office’s ‘New Burdens Assessment’ in 2015, 407 local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales are required to implement the Prevent Duty (Home Office, 2015d: 3). The de-radicalisation programme Channel is an essential part of the Prevent strategy:

Channel is a programme which focuses on providing support at an early stage to people who are identified as being vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism. The programme uses a multi-agency approach to protect vulnerable people by:

a. identifying individuals at risk;

b. assessing the nature and extent of that risk; and

c. developing the most appropriate support plan for the individuals concerned (Home Office, 2015c: 5)

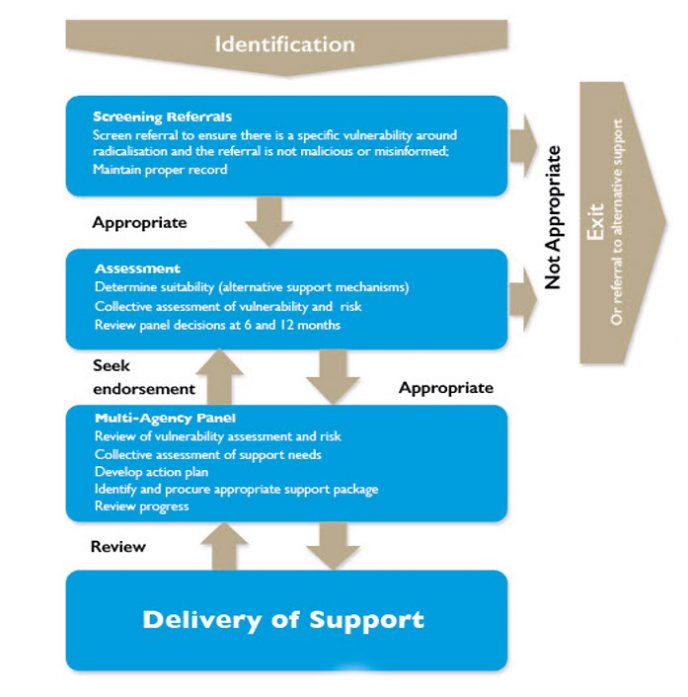

First piloted in 2007, Channel had been introduced as a voluntary programme, but was subsequently put on a statutory basis under the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 (Home Office, 2015a). As a multi-agency approach with a particular focus on ‘safeguarding’ vulnerable individuals, it requires cooperation between local Channel panels, local authorities (e.g. social and health services, educational institutions, etc.) and the police. While the programme, just like the overall Prevent strategy, aims at targeting all types of radicalisation, the government advises that “Channel programmes should be prioritised around areas of higher risk, defined as those where terrorist groups and their sympathisers have been most active” (Home Office, 2011b: 60). In practice, then, Channel initiatives are most likely to focus on the threat that has been identified as the most severe by the government, namely Muslim fundamentalism. The following diagram summarizes the different Channel stages as proposed by the Home Office:

Figure 1: The stages of Channel referrals

Arguably, the difficult task of identifying vulnerability to radicalisation in students represents the crux of the matter. With an overall goal of having no “‘ungoverned spaces’ in which extremism is allowed to flourish without firm challenge and, where appropriate, by legal intervention” (Home Office, 2011b: 9), the successful implementation of Prevent is greatly dependent on the support and engagement of local authorities.

The Prevent Duty

In July 2015, as an extension of the overall Prevent strategy, the UK government introduced the Prevent Duty in order to tackle radicalisation within ‘specified authorities’ (e.g. educational institutions). Due to an emphasis on preventing radicalisation in young individuals, the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 placed a statutory duty on specified authorities “to have due regard to the need to prevent people being drawn into terrorism” (OSCB, 2016). It is this ‘due regard’ – the Prevent Duty – that has been subject to fierce controversy. One of those specified authorities are schools, where teachers now have the statutory duty to detect radicalisation in the form of ‘violent’ and ‘non-violent’ extremism. If teachers suspect pupils to be vulnerable to radicalisation, they are required to report them and to cooperate with the police as well as the Channel boards (Open Justice Initiative, 2016: 3). Targeting both ‘violent’ and ‘non-violent’ extremism, the Prevent Duty serves the purpose of intercepting the rise of radical ideology in its early stages.

Even though the Prevent Duty claims to have the primary goal of safeguarding vulnerable individuals, it has been subject to substantial criticism. According to the Open Justice Initiative’s executive summary ‘Eroding Truest: The UK’s PREVENT Counter-Extremism Strategy in Health and Education’, the Prevent Duty suffers from structural flaws including “the targeting of “pre-criminality”, “non-violent extremism”, and opposition to “British values”” (Open Justice Initiative, 2016: 4). Among the plethora of criticisms, three alleged shortcomings are most frequently mentioned: the potentially chilling effect on human rights caused by structural flaws such as the broad definition of ‘non-violent extremism’; the discriminatory potential against Islam and, in particular, against Muslim youths; and the paradoxical relationship of the two co-existing statutory duties of ‘safeguarding’ (i.e. protecting) children ‘at risk’ and reporting ‘risky’ children.

Ambiguous Terminology: ‘Radicalisation’ and ‘Extremism’

Given that ideology is delineated as the key factor in the process of radicalisation (Home Office, 2011b: 44), the Prevent Duty guidance provided defines radicalisation as referring “to the process by which a person comes to support terrorism and extremist ideologies associated with terrorist groups” (Home Office, 2015b: 21). The logic of this description of radicalisation as a process is unsurprising; by definition, a process allows for governmental intervention (Heath-Kelly, 2013: 394) or disruption (Innes, Roberts and Lowe, 2017: 266).

The terminology of radicalisation has been subject to considerable scholarly debate, which oscillates between classifying it either as a propaganda myth (Hoskins and O’Loughlin, 2009: 107) or as an ambiguous, but dominating concept:

Rather than denying its validity, […] scholars and policy makers […] [should] work harder to understand and embrace a concept which – though ambiguous – is likely to dominate public discourse, research and policy agendas for years to come (Neumann, 2013: 874).

It can be argued that radicalisation is a relational concept. The term ‘radical’ does not necessarily convey any meaning in isolation. In fact, its connotation depends to a great extent on what the majority of society defines as ‘mainstream’ or ‘normal’ (Neumann, 2013). Detecting radicalisation in individuals, then, is contextually dependant on what the majority of people perceive as ‘normal’. Naturally, such perceptions are rather subjective and can vary from one individual to another – thereby holding the potential to destabilise the concept of radicalisation. This is precisely why scholars such as Richards (2011) question the overall utility of the radicalisation terminology, claiming that “there is little discernible value in using the idea of ‘radicalization’ to enhance our knowledge of why people become terrorists” as well as that “it has served to blur the counterterrorist response” (Richards, 2011: 145). Richard’s claim addresses a central paradox of the Prevent Duty: while schools are instructed to tackle radicalisation, the list of radicalisation indicators provided by the Home Office is blurry at its best, and highly misleading at its worst.

What the definitional confusion regarding radicalisation may be concerned with is not so much the term itself, but rather its relational content; first, the distinction between cognitive and behavioural radicalisation, and second, the element of ‘non-violent’ extremism. While the Home Office argues that the official definition of radicalisation includes both the cognitive as well as the behavioural dimension (Home Office, 2011: 56), this approach has been criticised by certain academics, e.g. Horgan (2012; 2013) and Borum (2011). In short, both scholars contend that a focus on the cognitive dimension of radicalisation risks misplaces counter-terrorism responses due to the fact that not every person classified as ideologically radical will turn into a violent extremist and/or terrorist. The criticism of tackling cognitive radicalisation stems from repeated unsuccessful psychological attempts to profile terrorists (Horgan, 2008: 80). After the 7/7 bombings, a House of Commons Report stated that “[w]hat we know of previous extremists in the UK shows that there is not a consistent profile to help identify who may be vulnerable to radicalisation” (House of Commons, 2006: 31). Instead of seeking for root causes of radicalisation, Horgan (2008) contends that a focus on behavioural pathways and routes to terrorism may prove more valuable for targeting radicalisation.

Arguably, despite claiming to target both cognitive and behavioural radicalisation, the government’s counterterrorism strategy may suffer from a predominantly ideological approach and thus be ill-equipped to thoroughly address the overall process of radicalisation. It is time to reject the myth that radicalisation solely occurs “by developing or adopting extremist beliefs that justify violence” and come to terms with the reality that this is just one of many pathways into terrorism (Borum, 2011: 8). Most academic radicalisation models (e.g. Moghadam’s ‘staircase model’, or Baran’s ‘conveyor belt’ model) take into account multiple push and pull factors of radicalisation, thereby recognising the conceptual validity of radicalisation as a process (Elshimi, 2017). Similar claims were made by Borum (2011) after conducting a systematic literature review: according to his findings, factors such as perceived injustice, struggles of identity, as well as the desire for belonging were crucial predictors of radicalisation and extremist engagement. Consequently, it can be agreed that adopting a more holistic approach to radicalisation as advocated by Neumann (2013) or Elshimi (2017) is best equipped to detect and prevent radicalisation and extremism. In practice, this would entail to ‘have due regard’ to signs of both cognitive and behavioural radicalisation in relatively equal parts. Nonetheless, the reality of detecting radicalisation, especially in youths, remains a complicated endeavour. According to the Oxfordshire City Council, changes in behaviour or attitude can include the following:

withdrawal from usual activities; expressing feelings of anger, grievance or injustice; truanting / going missing from school or care; expressing ‘them and us’ thinking; using inappropriate language and / or advocating violent actions and means’ possessing extremist literature and / or expressing extremist views; associating with known extremists; seeking to recruit others to an extremist ideology (Oxfordshire City Council, 2017).

Having ‘due regard’ to the above radicalisation indicators can potentially result in reporting teenagers for puberty-typical behaviour such as ‘expressing feelings of anger’ or ‘using inappropriate language’. As mentioned within the prior chapter, the Prevent Duty guidance provides an extremely broad definition of ‘due regard’:

the authorities should place an appropriate amount of weight on the need to prevent people being drawn into terrorism when they consider all the other factors relevant to how they carry out their usual functions (Home Office, 2015b: 36).

It remains unclear what precisely is regarded as ‘an appropriate amount’ – thereby leaving the implementation of the Prevent Duty up to the discretion of staff members. In addition to these already vague instructions, ‘non-violent extremism’ is delineated as “extremism […] which is not accompanied by violence” (Home Office, 2015b: 36). ‘Extremism’, then, the Home Office views as synonymous to

vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also include in our definition of extremism calls for the death of members of our armed forces, whether in this country or overseas (Home Office, 2015b: 36).

It comes as no surprise that such vague definitions have caused great academic controversy. The notion of ‘non-violent’ extremism reinforces the government’s ideological focus by targeting an opposition to ‘British values’, which can potentially be challenged and opposed in many different ways. According to Ramsay (2017: 14), this definition is “literally expansive in the sense that it is non-exhaustive” due to the fact that it identifies only some values which are part of “a list of what British values ‘include’, [thereby] suggesting that there may be other unspecified ‘fundamental British values’”. This does not only enable a great extent of, first, uncertainty and, second, discretion for educational staff who are required to have ‘due regard’, but, in practice, depends on “the views and prejudices of the staff member involved in the surveillance of students’ conduct and speech” (Ramsay, 2017: 14) Essentially, the definition of radicalisation remains a grey area, and has been under attack for having a chilling effect on human rights such as the freedom of expression:

[t]here are many people who oppose democracy; there are people who have alternative views on that: does that mean that they are never allowed to express those views[…], as part of an open discussion on these issues? (Baroness Warsi, Lords Hansard, 2015: Column 222).

With the government claiming that it is not always “desirable to draw clear lines” between terrorism and extremism (Home Office, 2011: 25), a rather questionable linear relationship between ideological extremism and terrorism is invoked, which could contribute to further problematising the identities of British Muslims (Spalek, 2011).

The Implementation of Prevent in Educational Institutions

‘Safeguarding’ and safe spaces

In line with the programme’s second and third objective – to “prevent people from being drawn into terrorism and ensure that they are given appropriate advice and support; and work with sectors and institutions where there are risks of radicalisation which we need to address” (Home Office, 2011b: 7) – the Prevent Duty relies on the terminology of ‘safeguarding’ children by providing safe spaces. Arguably, the phrase safe space has become an “overused but undertheorized metaphor” (Barrett, 2010: 1). The Oxford Dictionary defines a safe space as “[a] place or environment in which a person or category of people can feel confident that they will not be exposed to discrimination, criticism, harassment, or any other emotional or physical harm” (Oxford Dictionary, n.d.). This original definition can be understood as the first layer to the definition of safe spaces; a space where no one is harmed or discriminated against. The second layer of safe spaces crystallizes in form of the statutory duty requiring educational institutions to

[protect] children from maltreatment; [prevent] impairment of children’s health or development; [ensure] that children are growing up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care; and [take] action to enable children in need to have optimum life chances (OSCB, n.d.: 1).

This second dimension of safe spaces represents the obligation of schools in England and Wales to safeguard the child’s welfare (Children Act 2004, Chapter 31, Section 11(2a) and 28(2a)).

In short, the Prevent Duty adds another layer to the above established typology of safe spaces. The particular language use of ‘safeguarding’ and safe spaces – terms already familiar to educational institutions – has been criticised as a governmental means to legitimise the Prevent Duty, circumvent resistance and, thus, allowing for a relatively smooth implementation in educational institutions (Ramsay, 2017). At the issue’s core lies the question whether the Prevent Duty, by enforcing the element of surveillance in the classroom, undermines the trust between teachers and students (Marsden, 2015).

Similar to radicalisation, safe spaces are a relational concept, with their underlying definition largely depending on the key question of what makes safe spaces necessary to begin with. It is the nature of the harm or threat that defines safe spaces. The required measures of coercion – such as potential referrals to Channel – could end up having a reverse effect (e.g. students do not voice their grievances). While the potential threat to ‘inclusive’ safe spaces in classrooms materialises in form of discrimination or harassment, the threat targeted by the Prevent duty is identified as extremist views and possible radicalisation. Arguably, both educational safeguarding duties (‘inclusive safe spaces’ and the Prevent Duty) share the same rationale, namely a “commitment to protecting vulnerable people from the potential ill-effects of others’ dangerous or offensive opinions” (Ramsay, 2017: 4). Further analysis of these issues is provided in chapter 3.4 against the backdrop of individuals caught in the terminological triangle of ‘vulnerable – at risk – riskiness’.

Referrals to the Channel Programme

As part of the overarching Prevent strategy, the de-radicalisation programme Channel is a tool to tackle extremism before it can grow into extremist or violent behaviour. According to the Home Office, Channel is meant to be

a multi-agency approach to identify and provide support to individuals who are at risk of being drawn into terrorism. […] Channel is about ensuring that vulnerable children and adults of any faith, ethnicity or background receive support before their vulnerabilities are exploited by those that would want them to embrace terrorism, and before they become involved in criminal terrorist related activity” (Home Office, 2012: 4).

In order to evaluate how this affects the statutory Prevent Duty in educational institutions, two key elements have to be considered: firstly, the use of the term ‘vulnerable’, and secondly, to what extent Channel referrals are utilised for children in educational institutions.

First, the carefully employed terminology conceals that children are not only considered ‘vulnerable’ and ‘at risk’, but are simultaneously viewed as ‘risky’ (i.e. they could potentially become a threat) (Aradau, 2004; Heath-Kelly, 2013). This dual role – which most students would not even be aware of – is difficult to address for educational institutions. Secondly, as part of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, Channel has become a legal requirement and is thus subject to a statutory framework rather in form of the exercise of ‘soft power’. Under the statutory Prevent Duty, educational institutions can place referrals to Channel if they fear that certain individuals are at risk of being drawn into extremism (OSCB, 2016). Referrals are assessed by the local Channel boards, consisting of school representatives, social workers, chairs of local Safeguarding Children Boards and Home Office Immigration as well as Border Force officials (Home Office, 2015c: 7). One of the key questions, however, is what happens to individuals once they have been referred to the Channel programme. According to Kundnani, Channel

[…] sought to profile young people who were not suspected of involvement in criminal activity but nevertheless were regarded as drifting towards extremism. Through an extensive system of surveillance involving, among others, police officers, teachers, and youth and health workers, would-be radicals were identified and given counselling, mentoring, and religious instruction in an attempt to reverse the radicalisation process. In some cases individuals were rehoused in new neighbourhoods to disconnect them from local influences considered harmful (Kundnani, 2014: 154).

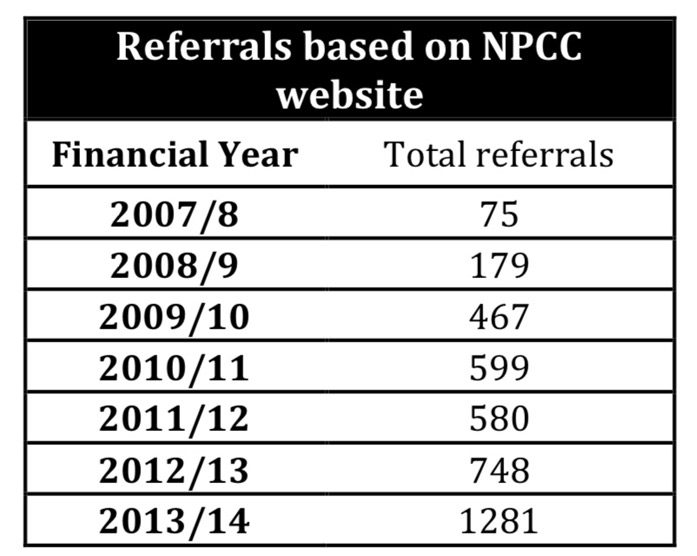

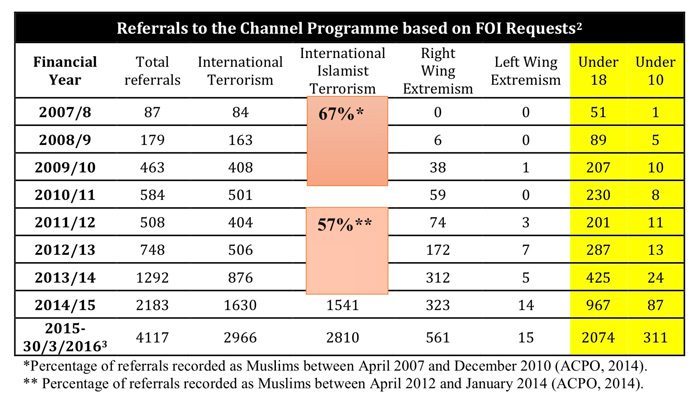

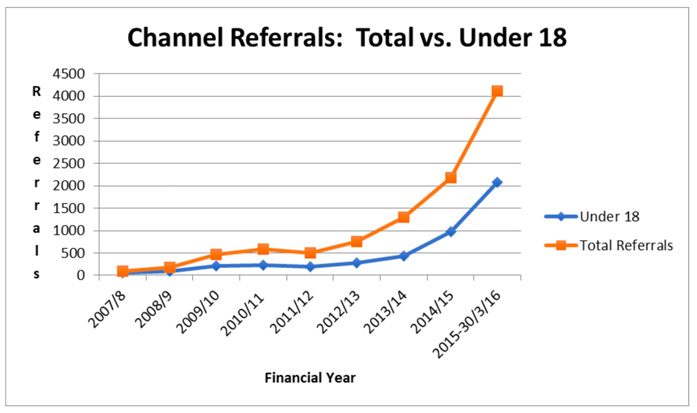

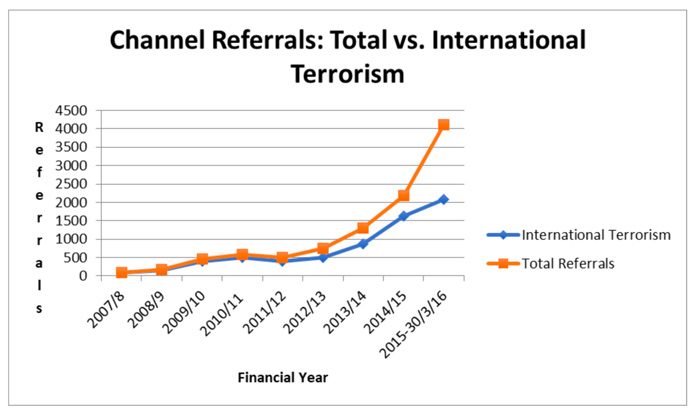

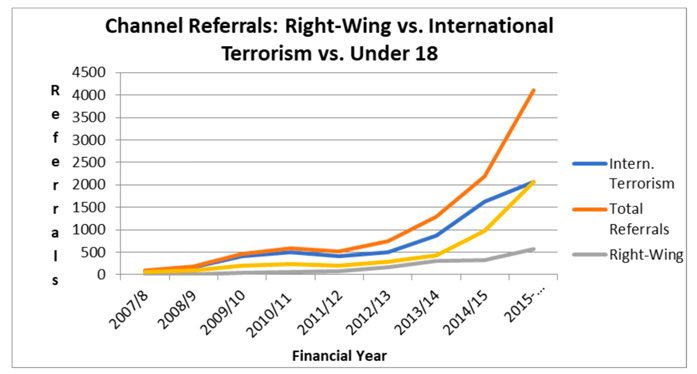

Evidently, referring youths to the Channel programme may trigger far-reaching consequences. Since the Prevent strategy’s introduction, the number of referrals to Channel has steadily risen: as can be seen in the Figure 4, the number of total referrals almost doubled from the year 2013/14 to 2014/15 and then again from 2014/15 to 2015-30/2/16. However, comparing the published Freedom of Information (FOI) Requests (Figure 4) with numbers published on the NPCC website (Figure 3), reveals a disparity in numbers. Due to a lack of background information (and the odd fact that the numbers of both Figure 3 and Figure 4 have been published by the NPCC), these variations cannot be explained.

According to a FOI request published by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) in 2014, 67 percent of the referrals between April 2007 and December 2010 were recorded as Muslim. Other FOI requests do not indicate the number of Muslim referrals between 2007/8 and 2010/11. Between April 2012 and January 2014, 57 percent of referrals were recorded as Muslim. Due to the variation in data sets published on the NPCC website and in FOIs (also on the NPCC website), these numbers are by no means absolute. Despite this limitation, they can still serve as a valid reference point to get a general understanding of the proportions of referrals to local Channel boards. Notwithstanding the Prevent strategy’s claim to tackle all extremism, the reality of Channel referrals paints a rather different picture. In comparison, local authorities appear to be placing significantly fewer referrals for right or left-wing extremism than for international terrorism. Regarding the practice of the Prevent Duty in educational institutions, another FOI Request published by the NPCC indicates that the number of referrals made by schools between April 2012 and April 2016 is 1494 (NPCC, 2016b: 2). According to a 2016 Guardian article on the Prevent Duty and Channel referrals, teachers were responsible for one-third of all Channel referrals in 2015 – which, it is argued, can be ascribed to “nervousness about missing signs of vulnerability” and “reporting incidents out of fear that they would be blamed if they failed to spot a student at risk” (Radcliffe, 2016).

Figure 3 and 4: Referrals to Channel

*Percentage of referrals recorded as Muslims between April 2007 and December 2010 (ACPO, 2014).

** Percentage of referrals recorded as Muslims between April 2012 and January 2014 (ACPO, 2014).

The high number of referrals of under 18-year-olds discloses the Prevent strategy’s focus on young individuals at the risk of radicalisation (Figure 4; Figure 5). Despite the fact that the Prevent Duty applies to several local authorities (e.g. the NHS, social workers, schools) and the above figures refer to Channel referrals placed from all sort of institutions, schools appear to be responsible for a plenitude of referrals. This further reinforces the need to scrutinise the implications of the Prevent Duty in educational institutions. Figure 5 (based on Figure 4) provides an approximate visualisation of the under-18 referrals compared to the total referrals between 2007/8 and the 30/3/2016.

Figure 5: Channel Referrals: Total vs. Under 18

Figure 6: Referrals to Channel: Total vs. International Terrorism

While Figure 5 concentrates on referrals of children and teenagers, Figure 6 displays the approximate proportion of individuals reported for suspected International Terrorism. Both graphs elucidate the primary focus on ‘Under 18’ and ‘International Terrorism’ referrals to Channel – meaning that both of these – potentially overlapping – categories require specific attention. Despite the lack of data on referrals specifically designated as ‘International Islamist Terrorism’, it is likely that these numbers are to a great extent swallowed by the ‘International Terrorism’ category.

Figure 8: Channel Referrals: Right-Wing vs. International Terrorism vs. Under 18

In addition to the fact that the overall Channel referrals have been subject to a significant increase from 2013 to 2016, it can be seen that the referrals reported as ‘International Terrorism’ are significantly higher than all others – with the exception of the last year, where the ‘Under 18’ referrals were equally substantial (and presumably overlapping).

It has to be noted that the label ‘International Terrorism’ does not necessarily verify whether referrals were reported as Muslim or not. Only incomplete information is available on the amount of referrals categorised as ‘International Islamist Terrorism’: according to a Freedom of Information Request published by the ACPO in 2014, 67 percent of all referrals between April 2007 and December 2010 and 57 percent of all referrals between April 2012 and January 2014 were recorded as Muslim (ACPO, 2014). How many of these referrals are also categorised as ‘International Terrorism’ or ‘Under 18’ – or both – remains unclear. Yet, the comparatively high percentages of referrals recorded as Muslim indicate that, in practice, the Prevent strategy and Duty primarily target the Muslim population. The targeting of Muslims seems even more disproportionate considering the fact that, according to the Annual Population Survey for England and Wales, only 5.6 percent of the English and 1.5 percent of the Welsh population reported their religion as Muslim in 2014 (Office for National Statistics, 2016).

Vulnerability to radicalisation: A double-edged sword?

The multi-layered concept of vulnerability is best assessed by taking a closer look at the notion of the Prevent Duty as a safe space in educational institutions. Equating the statutory duty with ‘safeguarding’ vulnerable students has been subject to heated controversy: treating students as vulnerable individuals who are simultaneously ‘at risk’ and ‘risky’ (Ramsay, 2017), the Prevent Duty has been criticised for “blurring […] vulnerability into presumed riskiness” (Heath-Kelly, 2013: 406). What is more, it has been under attack for bringing “state coercion into the educational space” (Ramsay, 2017: 16) and thereby preventing the very safe spaces of education that it seeks to facilitate. In order to investigate this criticism more in-depth, Ramsay’s (2017) comparison of educational safe spaces and the Prevent duty proves particularly useful.

In line with the second objective to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism, the Home Office provides the following definition for vulnerability:

[a]pologists for violent extremism very often target individuals who, for a range of reasons, are vulnerable to their messages. Vulnerability is not simply a result of actual or perceived grievances. It may be the result of family or peer pressure, the absence of positive mentors and role models, a crisis of identity, links to criminality including other forms of violence, exposure to traumatic events (here or overseas), or changing circumstances (e.g. a new environment following migration and asylum)” (Home Office, 2009: 89).

The multitude of vulnerability indicators that educational staff are required to have ‘due regard’ to signals that vulnerability has “many dimensions” (Edwards, 2016: 301). Vulnerable individuals are described as ‘being at risk’ of ‘being drawn into’ terrorism – rendering them passive rather than active agents. It is important to recognise how the term ‘at risk’ removes the agency from vulnerable individuals, even though they are simultaneously perceived as having the potential to pose a threat to ‘British values’ and society.

Evoking the imagery of vulnerability as a ‘double-edged sword, the dual role of ‘risky-at-risk’ students casts doubt on the Home Office’s claim that “[s]afeguarding vulnerable people from radicalisation is no different from safeguarding them from other forms of harm” (Home Office, 2011). In this claim lies the crux of the whole safe spaces controversy: what is the difference between ‘inclusive safe spaces’ in classrooms and the safe spaces supposedly created by the Prevent Duty?

I argue that the terminology of safeguarding is misleading and conveniently inflated in order to legitimise the Prevent Duty. Both radicalisation and safe spaces are relational concepts, meaning that it is the practical context that has to be considered. Assessing whether Prevent creates educational safe spaces, Ramsay infers that “Prevent should […] be understood as one example of a much wider tendency of surveillance and regulation of speech”, subsequently arguing that

[t]he shared rationale of the two strategies indicates that Prevent draws its practical political legitimacy not from hostility to Muslims but from a much wider commitment to protecting vulnerable people from the ill-effects of others dangerous or offensive opinions (Ramsay, 2017: 3)

While it is generally true that both dimensions of safe spaces share the rationale of safeguarding individuals from dangerous opinions, a more in-depth comparison reveals practical differences with regards to both the harm to be prevented as well as the consequences of the strategy’s implementation. Ramsay’s (2017) analysis is mainly concerned with the Prevent Duty in higher education, however, most of his arguments are also applicable to schools.

The harms to be prevented by both the Prevent Duty and the educational ‘inclusive safe spaces’ share two common features: they are “vaguely and expansively defined” and aimed at “securing educational spaces” (Ramsay, 2017: 8) from an “unchallenged expression” of harmful ideas (Ramsay, 2017: 10). It is precisely the nature of the harm that distinguishes the two strategies: the harm or threat that ought to be prevented in classrooms is discriminatory harassment, while the harm targeted by the Prevent Duty takes the form of radicalisation and extremism. Notably, the ulterior motive for seeking to prevent the harm of radicalisation is ultimately to “pre-empt the further harms that may result from any violence arising from a student’s radicalisation” (Ramsay, 2017: 7). What matters, then, is again the relational context of vulnerability: in the case of classroom safe spaces, the student if vulnerable to harassment of discrimination, as opposed to the Prevent Duty identifying the student as vulnerable to becoming radicalised. Thus, in the latter case the student is vulnerable to becoming a threat (Ramsay, 2017: 7). In other words, it is essentially the double-edged nature of the term vulnerability, incorporated in the statutory duty of teachers to have ‘due regard’ to vulnerable students at the risk of being drawn into extremism, that may function as a misnomer masking the real intention of identifying those posing a terrorism threat.

By drawing on the terminology of educational safe spaces it transpires that the government may be interested in concealing the double-edged character of vulnerability under the Prevent Duty. Seemingly stripped of their agency, vulnerable students ought to be protected, just as it is laid out in the original ‘Statutory Guidance on Making Arrangements to Safeguard and Promote the Welfare of Children under Section 11 of the Children Act 2004’:

Consequently, staff in […] [schools] play an important part in safeguarding children from abuse and neglect by early identification of children who may be vulnerable or at risk of harm and by educating children about managing risks and improving their resilience through the curriculum (Statutory Guidance on Making Arrangements to Safeguard and Promote the Welfare of Children under Section 11 of the Children Act 2004, 2007: 36).

The vital definition that discerns safe spaces in the classroom lies within the emphasis on educating children: “by educating children […] and improving their resilience through the curriculum”. What follows is that ‘inclusive’ safe spaces are spaces where individuals should be able to

fully express, without fear of being made to feel uncomfortable, unwelcome, or unsafe on account of biological sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, cultural background, religious affiliation, age, or physical or mental ability (Safe Space Network, 2017).

Arguably, while the educational safe spaces adhere to the foregoing definition, the Prevent Duty fails to do so. Despite the government’s efforts to legitimise the Prevent Duty by drawing on the terminology of ‘inclusive’ safe spaces, the safe spaces created by Prevent introduce a dual role of ‘risky-at-risk’ students – thereby engendering very different consequences. Even though both safeguarding duties regulate the freedom of expression in certain ways, it can be argued that the Prevent Duty, as part of the government’s counterterrorism strategy, may entail comparatively far-reaching consequences if students are identified as vulnerable to radicalisation. One of these consequences may be the referral to a local Channel board. Uncertainty about the meaning of ‘non-violent extremism’ in combination with the vague definition of ‘British values’ renders it problematic to identify radicalisation in the first place – which is precisely why critics of the Prevent Duty fear that it may potentially be “counterproductive, having a chilling effect on the willingness of students and teachers to debate difficult questions” (Marsden, 2015).

There is a case to be made that the Prevent Duty may facilitate a different kind of safe space: due to the dual role of students as both vulnerable and a threat, and the perception of Islamist radicalism being the primary threat, it creates an ‘exclusive’ safe space, where students may refrain from raising controversial opinions about topics such as Islamism and extremism. While both the implementation of the Prevent duty as well as ‘inclusive’ safe spaces may share the common feature of regulating the freedom of expression, the chilling effect caused by the Prevent Duty could be more significant. It identifies students as vulnerable to ideas opposing ‘British values’, and lacks any easily discernible definition. Effectively, the ‘exclusive’ safe space created by the Prevent Duty adds the element of suppressive surveillance to the classroom rather than encouraging an engaging and inclusive debate. Possibly motivated by the desire to give legitimacy to the Prevent agenda, the Home Office’s claim that “[s]afeguarding vulnerable people from radicalisation is no different from safeguarding them from other forms of harm” (Home Office, 2011) turns out to be misleading and ill-informed. The consequences of enforcing ‘exclusive’ safe spaces under the Prevent Duty will be critically examined in the subsequent section.

‘Bestowing Mistrust’: The Prevent Duty in Practice

In theory, the non-statutory guidance for schools on the promotion of British values advises teachers to

ensure that all pupils within the school have a voice that is listened to, and demonstrate how democracy works by actively promoting democratic processes such as a school council whose members are voted for by the pupils (Department of Education, 2014: 6).

In reality, however, the Prevent strategy as well as the Prevent Duty have been criticised for “bestowing mistrust” in the Muslim community (Miqdaad Versi, quoted in Ullah, 2016) based on allegations that the Prevent strategy is discriminatory in nature and used to gather intelligence about Muslim students and communities (Home Office, 2011b). Such allegations indicate that Prevent has a rather negative impact on relationships with Muslim communities, thus failing at implementing the strategy’s third objective of promoting partnership work (Awan, 2012; Allen, 2011; Bonino, 2013; Qureshi, 2014; Spalek, 2011; Taylor, 2018). Despite this nexus of allegations as well as the Home Office’s realisation in 2011 that “[t]rust in Prevent must be improved” (Home Office, 2011b: 6), the wider political context recently contributed to an even more entrenched approach to the ‘good Muslim’/‘bad Muslim’ binary: on June 7, 2017, Theresa May announced that in the fight against terrorism, “things need to change” by providing security and intelligence agencies with “the powers they need”, subsequently stating that “[…] if our human rights laws get in the way of doing it, we will change the law so we can do it” (BBC News, 2017). May could have been referring to Article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the invocation of which would allow the UK to depart from specific parts of the ECHR in limited times of emergency (BBC News, 2017). May’s decision to make a case for departing from human rights law lead to significant resistance in the ranks of both Labour and Liberal Democrats, arguing that countering terrorism would not succeed “by ripping up basic human rights” (BBC News, 2017). Rather than a new response to the terrorism threat, May’s statements represent the continuation of a trend of political speeches and punitive populism calling for harsher counterterrorism measures.

On March 21, 2006, Tony Blair asserted that “[t]his terrorism will not be defeated until its ideas, the poison that warps the minds of its adherents, are confronted, head-on, in their essence, at their core” (HM Government, 2006: 10), which led the Home Office to the conclusion that countering terrorism materialises in form of

a battle of ideas, challenging the ideological motivations that extremists believe justify the use of violence. In particular, we are working with communities to help them discourage susceptible individuals from turning towards extremist activity (HM Government, 2006: 10).

Driven by the political agenda to govern ‘susceptible individuals’, i.e. to control individuals “at risk of becoming risky” (Heath-Kelly, 2013: 397), the Prevent Duty invokes a nebulous nexus of an ideological ‘battle of ideas’ against ‘non-violent extremism’ by promoting ‘British values’. It is this insidious system that holds significant potential to infringe on human rights, thereby bolstering the Prevent Duty’s ‘exclusive’ safeguarding practices. What further reinforces this chilling effect on human rights are the consequences of a failure to ‘have due regard to’ radicalisation in students, which is likely to “bring the attention of the state’s security bureaucracy” (Ramsay, 2017: 15).

Trying to prevent radicalisation in children and teenagers raises especially difficult questions: “[f]or example, how, in what ways and to what extent are ‘radicalised’ youth displaying ‘destructive emotions’ and in what ways are practitioners working with and trying to influence these?” (Spalek, 2010). The aforementioned binary definition of Islam in the UK in combination with ‘a battle of thoughts’ with its focal point of ‘non-violent extremism’ renders it problematic to differentiate between simply rebellious or radicalised teenagers. The online Prevent Duty toolkit for schools provided by the Oxfordshire Safeguarding Children Board (OSCB) pinpoints potential consequences of a flawed implementation:

Over-simplified assessments based upon demographics and poverty indicators have consistently demonstrated to increase victimisation, fail to identify vulnerabilities and, in some cases, increase the ability of extremists to exploit, operate and recruit (OSCB, 2016: 3)

However, applying the Prevent Duty in a non-biased manner may turn into an insurmountable task given the complexity and multitude of vulnerability indicators. Positioning themselves in a social world, young individuals’ identities are still forming and being formed. A survey conducted by Holley and Steiner (2005) reinforces the importance of ‘inclusive’ educational safe spaces: 121 Social Works baccalaureate and master students at a Western university were asked to define ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’ classroom environments. The majority of students described safe spaces as “nonjudgmental or unbiased” and unsafe spaces as involving instructors who “were critical of or chastised students; were biased, opinionated, or judgmental; and refused to consider others’ opinions” (Holley and Steiner, 2005: 57).

A report on the practical implications of the Prevent Duty in educational institutions by Busher, Choudhury, Thomas, and Harris (2017) underpins the claim that many teachers and students perceive the Prevent Duty’s impact on educational safe spaces as highly problematic. For their report, Busher et al. (2017) conducted in-depth interviews with 70 education professionals across 14 schools in West Yorkshire and London as well as with 8 local authority level Prevent practitioners working to support schools and colleges. In addition, a national online survey of school and college staff (n=225) and a series of feedback and discussion sessions with Muslim civil society organisations were carried out. Among other key results, the study found “a strong current of concern, particularly among BME respondents, that the Prevent duty is making it more difficult to foster an environment in which students from different backgrounds get on well with one another” (Busher et al., 2017: 6). While Busher et al. do acknowledge that their findings may be subject to a range of interpretations, they also conclude that the Prevent Duty could exacerbate feelings of stigmatisation among Muslim students (Busher et al., 2017: 7).

When providing oral evidence on the Counter-extremism Bill on March 9, 2016, the former Independent Reviewer of Terrorism David Anderson highlighted that the Prevent Duty is likely to induce the latter, ‘unsafe’ form of environment:

I remember talking to a lady in the north-west who teaches at a college for 16 to 19 year-olds. ISIS comes up quite often. She used to use that as an opportunity for a discussion: “What are they doing? Why are they using violence? Are there other ways of doing it? What about Martin Luther King? What about Mahatma Ghandi?” Someone mentioned the IRA. “Is that the same as ISIS?” You would have a discussion and the toxic views would come out, which would hopefully be blunted or neutralised – or at least the people who held those views would be given something else to think about. She says that if that happens now, you absolutely choke off the discussion because the teachers are watching their backs and they do not want to be reported (Anderson, Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2016: 4).

Precisely this repercussion of the Prevent Duty has the capacity not only of infringing on human rights but possibly also inhibiting a natural progression of identity formation in young individuals. After all, “[t]he question ‘Who am I?’ is one of the most challenging we can ask” (Marranci, 2007: 138) and is, to a great extent, both context-dependent and formed through interaction. Thus, the conjunction of the statutory duty to ‘have due regard’, the fear of Channel referrals and the ‘good Muslim/bad Muslim’ binary, is likely to have the reverse effect of fostering radicalisation in British Muslim youths. As Yaqoob asks, if schools are “reluctant to provide the space for sensitive discussions for fear of extremist’s accusations, where are these young people to go? Where will their views and concern get an airing?” (Yaqoob, 2008).

Discussion

The main issue of the Prevent Duty may just be that it has become counter-productive: “The focus on radicalization has both complicated the task of those engaged in community cohesion and generated fears of stigmatizing communities” (Richards, 2009: 152). Arguably, the Prevent Duty undermines the educationally envisioned ‘inclusive’ safe spaces, where students feel safe enough to speak freely and discuss controversial topics. The process by which the Prevent Duty inhibits these safe spaces is rooted in its potential to infringe on human rights, predominantly on the right to freedom of expression. Simultaneously, though, the Prevent Duty constructs a different kind of safe space, distinguishable by its ‘exclusive’ nature. The students’ dual role of being both vulnerable and a risk in combination with the perception of Islamist radicalism as the primary threat creates an ‘exclusive’ safe space, where students avoid raising controversial opinions due to potentially far-reaching consequences (not least being referred to Channel).

Recommendations: Engagement over Targeting

In the light of the recent terror attacks and the recommendation of Max Hill, the current Independent Reviewer of Terrorism, to critically review the Prevent strategy, it is vital to highlight that any changes to the Prevent strategy should be undertaken without repeating old mistakes. Already in 2010, Spalek suggested that

there needs to be much greater acknowledgment of the diversity of individuals within a particular social group and/or network, and also that the notion of empowerment needs to be unpicked, because empowering individuals in terms of their own personal, educational and other developments is not necessarily empowering the particular religious, political or other groups they belong to, nor is it empowering religious, political and other ideologies (Spalek, 2011: 201).

A more promising approach, then, consist of a shift in focus from a predominant ‘targeting’ of Muslim communities to ‘engaging’ with them.

Evidently, the Prevent strategy suffers from a widespread problem of perception or, as argued by the former Independent Reviewer of Terrorism, David Anderson: “[i]t is perverse that Prevent has become a more significant source of grievance in affected communities than the police and ministerial powers (Anderson, n.d.: 3). One of the key criticisms of Prevent appears to be its failure to engage communities, and particularly Muslim communities.

It is engagement that could serve as an important ingredient in tackling radicalisation. According to Horgan’s (2013) research on the de-radicalisation of former terrorists, a disengaged terrorist is not necessarily de-radicalised – meaning that the process of de-radicalisation may not have taken place, despite the individual’s apparent disengagement. He or she may still hold ‘radical’ opinions (Horgan, 2013: 19). Such findings support Spalek’s recommendation that the prevention of radicalisation and ‘home-grown’ terrorism can and should focus on the engagement of both the individual and communities (Spalek, 2011). Based on the Prevent strategy continuously failing to grapple with the criticism that “it enables the government to exclude potentially any Muslim group from engagement” (Spalek and McDonald, 2010: 128), what should follow is a focus on a bottom-up than top-down approach. This grassroots-approach would require a shift towards engagement, conversation and trust-building (Kundnani, 2009; Spalek, 2011). According to Kundnani (2009),

genuine trust can only come from the bottom up. So long as the government persists in a programme of imposing on its own citizens an ideological war over ‘values’ that is backed up with an elaborate web of surveillance, that trust will not be forthcoming. And those on the receiving end of such a programme will remain ‘spooked’ by fear, alienation and suspicion (Kudnani, 2009: 41).

In addition to a focus on trust-building, Horgan’s (2013) findings also draw attention to another relevant issue: engaging individuals considered as ‘radical’ or formerly ‘radical’ may be one of the key components that have to be addressed by any future revision of the Prevent strategy. While this may prove to be a rather complex endeavour, it first requires the terminological disconnection from ‘extremism’ and ‘radicalism’ – potentially by abandoning the term ‘non-violent extremism’.

The definition of ‘radical’ varies according to the shared norms of the majority of the population. In other words, individuals who are perceived to hold radical opinions may not necessarily qualify as extremists, or consider extremist means. This realisation renders the notion of non-violent extremism highly problematic, and possibly unpalatable against the backdrop of the right to freedom of expression and thought. In schools in particular, students need to be able to discuss sensitive matters and teachers “must have the integrity of their professional norms protected against the expectation that they become the eyes and ears of counterterrorist policing” (Kundnani, 2009: 7). Instead, by facilitating dialogue and debate, confidence in government initiatives may slowly be built, which could ideally result in the community cohesion that the UK urgently requires (Spalek and McDonald, 2010).

Rather than retaining the illusion that the Prevent strategy in its current state is capable of tackling radicalisation, the following three recommendations should be given priority:

- The widespread allegations about Prevent being a spying and surveillance programme have to be met with increased transparency. Arguably, a few decisive factors include better training for educational staff, the publication of training materials, as well as the regular publication of Channel referral numbers.

- What should be strongly encouraged is to diversify the “membership of the Prevent Advisory Boards” as well as the local Channel boards (Anderson, n.d.: 3).

- The Prevent strategy, including the Prevent Duty, should “be the subject of review by an independent panel with the relevant range of expertise, and with direct input from the internet generation” (Anderson, n.d.: 3).

Arguably, the third recommendation is paramount for future implementation of the Prevent Duty and the overall UK Prevent strategy.

Conclusion

The Prevent Duty in educational institutions is deeply flawed in its implementation, and may have significant potential to further alienate and radicalise the British Muslim population. Despite such worrying findings and the increasingly frequent occurrence of recent terror attacks in the UK, I agree that “optimism should be the exhortation. And for an optimistic future, both the mainstream societies as well as diaspora-based Muslim communities should realise that their common future would be shared” (Mukhopadhyay, 2007: 111). This shared future is best secured by standing firmly for the preservation of human rights, fostering constructive and engaging dialogue and defying the illusion that terrorism could be defeated by shutting down opposing opinions. Preventing challenging conversation is probably more likely to suspend radical opinions rather than tackle their root causes.

References

Abbas, T. (2007) ‘Introduction: Islamic Political Radicalism in Western Europe’, Abbas, T. (ed.) Islamic Political Radicalisation: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

ACPO (2014) Freedom of Information Request Reference Number 000117/13. Available from: http://www.npcc.police.uk/documents/FoI%20publication/Disclosure%20Logs/Uniformed%20Operations%20FOI/2013/117%2013%20ACPO%20Response%20-%20Channel%20Project%20Referrals.pdf. Last accessed: 10 May 2017.

Allen, C. (2011) ‘Against Complacency’, Soundings. Available from: https://wallscometumblingdown.wordpress.com/2011/06/09/against-complacency-new-article-on-the-mcbs-soundings/. Last accessed: 13 June 2017.

Anderson, D. (2017) ‘Prevent – Evening Standard op-ed’. Available from: https://terrorismlegislationreviewer.independent.gov.uk/prevent-evening-standard-op-ed/. Last accessed: 10 May 2017.

Anderson, D. (n.d.) ‘Supplementary Written Evidence submitted by David Anderson Q. C.: Lack of Confidence in Prevent’, Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation. Available from: http://togetheragainstprevent.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Written-evidence-submitted-by-David-Anderson-Q.C..pdf. Last accessed: 18 June 2017.

Aradau, C. (2004) ‘The perverse Politics of Four-Letter Words: Risk and Pity in the Securitisation of Human Trafficking’, Millennium Journal of International Studies 33(2): 251-278.

Awan. I. (2012) ‘“I am a Muslim Not an Extremist”: How the Prevent Strategy Has Constructed a “Suspect” Community’, Politics & Policy 40(6): 1158-1185.

Baran, Z. (2005) ‘Fighting the War of Ideas’, Foreign Affairs 84(6): 68-78.

Barrett, B. (2010) ‘Is “safety” dangerous? A critical Examination of the Classroom as Safe Space”, The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 1(1): 1-12.

BBC News (2017) ‘Theresa May: Human Rights Laws could change for Terror Fight’, BBC News. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2017-40181444. Last accessed: 13 June 2017.

BMFSFJ (2017) ‘Bericht der Bundesregierung über Arbeit und Wirksamkeit der Bundesprogramme zur Extremismusprävention’. Available from: https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/116788/354cf0b045adc89e2a07968851334c8d/bericht-extremismuspraevention-data.pdf. Last accessed: 12 April 2018.

Bonino, S. (2013) ‘Prevent-ing Muslimness in Britain: The Normalisation of Exceptional Measures to Combat Terrorism’, Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 33(3): 385-400.

Borum, R. (2011) ‘Radicalization into violent extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories’, Journal of Strategic Security 4(4): 7-36.

Busher, J., Choudhury, T., Thomas, P., & Harris, G. (2017). What the Prevent duty means for schools and colleges in England: An analysis of educationalists’ experiences. Available from http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/32349/. Last accessed: March 2018.

Children Act 2004. London: HM Government. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/31/pdfs/ukpga_20040031_en.pdf. Last accessed: 11 June 2017.

Cole, D. (2009) ‘English Lessons: A Comparative Analysis of UK and US Responses to Terrorism’, Current Legal Problems 62(1):136-167.

Council of Europe (1994), European Convention on Human Rights. Available from: http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf. Last accessed: 25 June 2017.

Dawson, J. and Pepin, S. (2017) Implementation of the Prevent Strategy. London: House of Commons Library, Available from: https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjYsZLdzNvUAhVILFAKHRKzCg0QFggoMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fresearchbriefings.files.parliament.uk%2Fdocuments%2FCDP-2017-0036%2FCDP-2017-0036.pdf&usg=AFQjCNE2FTAXIMAI-4nXsFhUoHUZB5-i_Q. Last accessed: 2 June 2017.

Department for Education (2014) Promoting Fundamental British Values as Part of SMSC in schools: Departmental Advice for Maintained Schools. London: Department for Education. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/380595/SMSC_Guidance_Maintained_Schools.pdf. Last accessed: 13 June 2017.

Edwards, P. (2016) ‘Closure through Resilience: The Case of Prevent’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39(4): 292-307.

Elshimi, M. S. (2017). De-radicalisation in the UK Prevent Strategy: Security, Identity, and Religion. London ; New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Heath-Kelly, C. (2013) ‘Counter-Terrorism and the Counterfactual: Producing the ‘Radicalisation’ Discourse and the UK Prevent Strategy’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations 15: 394-415.

Hill, M. (2017) ‘The London Bridge/Borough Market Attack, and the PM’s Announcement’, The Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation. Available from: https://terrorismlegislationreviewer.independent.gov.uk/. Last accessed: 18 June 2017.

HM Government (2006) Countering International Terrorism: The United Kingdom’s Strategy, CM 6888. London: HM Government, Available from: http://www.iwar.org.uk/homesec/resources/uk-threat-level/uk-counterterrorism-strategy.pdf. Last accessed: 9 June 2017.

HM Government (2007) Statutory Guidance on Making Arrangements to Safeguard and Promote the Welfare of Children under Section 11 of the Children Act 2004. London: Department for Education and Skills. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eorderingdownload/dfes-0036-2007.pdf. Last accessed: 11 June 2017.

Holley, L.C. and Steiner, S. (2005) ‘Safe space: Student Perspectives on Classroom Environment’, Journal of Social Work Education 41(1): 49-64.

Home Office (2009) Pursue, Prevent, Protect, Prepare: The United Kingdom’s Strategy for Countering International Terrorism, CM 75547. London: HM Government, Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228644/7547.pdf. Last accessed: 9 June 2017.

Home Office (2011a) CONTEST: The United Kingdom’s Strategy for Countering Terrorism. London: HM Government, Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/97994/contest-summary.pdf. Last accessed: 21 May 2017.

Home Office (2011b) Prevent Strategy. London: HM Government, Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/97976/prevent-strategy-review.pdf. Last accessed: 01 June 2017.

Home Office (2015a) Counter-Terrorism and Security Act. London: HM Government, Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/counter-terrorism-and-security-bill. Last accessed: 20 May 2017.

Home Office (2015b) Revised Prevent Duty Guidance: for England and Wales. London: HM Government, Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445977/3799_Revised_Prevent_Duty_Guidance__England_Wales_V2-Interactive.pdf. Last accessed: 28 May 2017.

Home Office (2015c) Channel Duty Guidance: Protecting Vulnerable People from being drawn into Terrorism. London: HM Government, Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425189/Channel_Duty_Guidance_April_2015.pdf. Last accessed: 02 June 2017.

Home Office (2015d) Prevent New Burdens Assessment. London: HM Government. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/438828/Prevent_Duty_-_New_Burdens_Assessment_-_Annex_A.pdf. Last accessed: 21 June 2017.

Home Office & Foreign Commonwealth Office (2004) Young Muslims and Extremism, cited in Mukhopadhyay, A. R. (2007) ‘Radical Islam in Europe: Misperceptions and Misconceptions’, Abbas, T. (ed.) Islamic Political Radicalisation: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Horgan, J. (2008) ‘From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives from Psychology on Radicalization into Terrorism’ The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618: 80-94.

Horgan, J. (2009) ‘Leaving Terrorism Behind: Individual and Collective Disengagement’. Presented at the International Studies Association Annual Meeting, New York, Available from: http://www.start.umd.edu/publication/leaving-terrorism-behind-individual-and-collective-disengagement. Last accessed: 05 June 2017.

Horgan, J. (2012) ‘Discussion Point: The End of Radicalization?’ START, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, Available from: http://www.start.umd.edu/news/discussion-point-end-radicalization, Last accessed: 05 June 2017.

Horgan, J. (2013) ‘Individual Disengagement: A Psychological Analysis’, Horgan, J. and Bjorgo, T. (eds.) Leaving Terrorism Behind: Individual and Collective Disengagement. London: Routledge.

Hoskins, A. and Loughlin, B. (2009) ‘Media and the Myth of Radicalization’, Media, War and Conflict 2(2): 107-110.

House of Commons (2006), Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005. London: The Stationery Office.

Innes, M., Roberts, C., & Lowe, T. (2017). A Disruptive Influence? “Prevent-ing” Problems and Countering Violent Extremism Policy in Practice. Law & Society Review, 51(2): 252-281.

Jackson, R. (2011) ‘Prevent: The Wrong Paradigm for the Wrong Problem’, richardjacksononterrorismblog. Available from: https://richardjacksonterrorismblog.wordpress.com/2011/06/09/prevent-the-wrong-paradigm-for-the-wrong-problem/. Last accessed: 13 June 2017.

Jackson, R. and Sinclair, S. J. (2012) ‘Introduction’, Jackson, R. and Sinclair, S. J. (eds.) Contemporary Debates on Terrorism. London: Routledge.

Kundnani, A. (2009) Spooked! How not to prevent Violent Extremism. London: Institute of Race Relations.

Kundnani, A. (2014) The Muslims are Coming. New York: Verso.

Lords Hansard (2015) Daily Hansard 28 January 2015. Parliament UK, Available from: https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201415/ldhansrd/text/150128-0001.htm. Last accessed: 03 June 2017.

Marranci, G. (2007) ‘From the Ethos of Justice to the Ideology of Justice’, Abbas, T. (ed.) Islamic Political Radicalisation: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Marsden, S. (2015) ‘Preventing ‘Violent Extremism’: Creating Safe Spaces for Negotiating Difference’, Political Studies Association. Available from: https://www.psa.ac.uk/insight-plus/preventing-violent-extremism-creating-safe-spaces-negotiating-difference. Last accessed: 11 June 2017.

Moghadam, F. (2005) ‘The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration’, American Psychologist 60(2): 161-169.

Mukhopadhyay, A. R. (2007) ‘Radical Islam in Europe: Misperceptions and Misconceptions’, Abbas, T. (ed.) Islamic Political Radicalisation: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) (2016) The Threat of Terrorism: How Should British Muslims Respond? – A Progress Report, Available from: http://www.mcb.org.uk/the-threat-of-terrorism-how-should-british-muslims-respond-a-progress-report/. Last accessed: 1 June 2017.

National Archives (2000) ‘Terrorism Act 2000’. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/11/contents. Last accessed: 25 June 2017.

Neumann, P. R. (2009) Old and New Terrorism. Cambridge: Polity.

Neumann, P. R. (2013) ‘The Trouble with Radicalization’, International Affairs 89(4): 873-893.

Nielsen, J. S. (2007) ‘The Discourse of ‘Terrorism’ between Violence, Justice and International Order’, Abbas, T. (ed.) Islamic Political Radicalisation: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

NPCC (2016a) ‘Freedom of Information Request Reference Number 000026/16’. Available from: http://www.npcc.police.uk/Publication/NPCC%20FOI/CT/02616ChannelReferrals.pdf. Last accessed: 10 May 2017.

NPCC (2016b) ‘Freedom of Information Request Reference Number 000097/16’. Available from: http://www.npcc.police.uk/FreedomofInformation/counterterrorism/2016.aspx. Last accessed: 08 June 2017.

Open Justice Initiative (2016) ‘Eroding Trust: The UK’s PREVENT Counter-Extremism Strategy in Health and Education’, Open Society Foundations. Available from: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/eroding-trust-20161017_0.pdf. Last accessed: 26 June 2017.

Office for National Statistics (2016) ‘Annual Population Survey Data for England and Wales’, London: ONS. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/adhocs/005254annualpopulationsurveydataforenglandwalesandselectedlocalauthoritiesshowingtotalpopulationandthosewhoreportedtheirreligionasmuslimfortheperiods2011to2014. Last accessed: 19 June 2017.

OSCB (2016) ‘Prevent Extremism’. Available from: http://www.oscb.org.uk/themes-tools/prevent-extremism/. Last accessed: 17 May 2017.

OSCB (n.d.) ‘Prevent Within Schools: Prevent & Channel Duty – A Toolkit for Schools’. Available from: http://www.oscb.org.uk/themes-tools/prevent-extremism/. Last accessed: 14 June 2017.

Oxford Dictionary (2017) ‘Definition: Safe Space’. Available from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/safe_space. Last accessed: 06 June 2017.

Oxfordshire City Council (2017) ‘Safeguarding Vulnerable People from Extremism’. Available from: https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/content/safeguarding-vulnerable-people-extremism. Last accessed: 15 May 2017.

Qureshi, A. (2015) ‘PREVENT: Creating ‘Radicals’ to strengthen Anti-Muslim Narratives’, Critical Studies on Terrorism 8(1): 181-191.

Radcliffe, R. (2016) ‘Teachers made one-third of referrals to prevent strategy in 2015’, The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jul/12/teachers-made-one-third-of-referrals-to-prevent-strategy-in-2015?CMP=share_btn_tw. Last accessed: 10 June 2016.

Ramsay, P. (2017) ‘Is Prevent a Safe Space?, Education, Citizenship and Social Justice: 1-30.

Richards, A. (2011) ‘The Problem with ‘Radicalisation’: The Remit of ‘Prevent’ and the Need to Refocus on Terrorism in the UK’, International Affairs 87(1): 143-152.

Safe Space Network (2017) ‘What is a Safe Space?’. Available from: http://safespacenetwork.tumblr.com/Safespace. Last accessed: 11 June 2016.

Spalek, B. (2010) ‘Opinion: Softly, softly: Working with communities to counter extremism’, Global Uncertainties: Schools’ Resource, Available from: http://www.debatingmatters.com/globaluncertainties/opinion/softly_softly_working_with_communities_to_counter_extremism/. Last accessed: 11 May 2017.

Spalek, B. (2011) ‘‘New Terrorism’ and Crime Prevention Initiatives involving Muslim Young People in the UK: research and Policy Contexts’, Religion, State and Society 39: 191-207.

Spalek, B. and McDonald, L. Z. (2010) ‘Terror Crime Prevention: Constructing Muslim Practices and Beliefs as ‘Anti-Social’ and ‘Extreme’ through CONTEST 2”, Social Policy and Society 9(1): 122-133.

Taylor, J. D. (2018). ‘Suspect Categories,’ Alienation and Counterterrorism: Critically Assessing PREVENT in the UK. Terrorism and Political Violence: 1-23.

The Roestone Collective (2014) ‘Safe Space: Towards a Reconceptualization’, Antipode 46(5): 1346–1365.

Thomas, P. (2009) ‘Between Two Stools? The Government’s ‘Preventing Violent Extremism’ Agenda’, The Political Quarterly 80(2): 282-291.

Ullah, A. (2016) ‘Muslim Council of Britain set to Launch Alternative to Prevent’, Middle East Eye. Available from: http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/muslim-council-britain-launches-new-version-prevent-632323768. Last accessed: 13 June 2017.

Yaqoob, S. (2007) ‘British Islamic Political Radicalism’, Abbas, T. (ed.) Islamic Political Radicalisation: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Yaqoob, S. (2008) ‘Government’s PVE Agenda is failing to tackle Extremism’, Muslim News. Available from: http://muslimnews.co.uk/paper/?article=3795. Last accessed: 01 April 2017.