“Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army have been abducting, killing, and displacing civilians in East and central Africa since 1987. We first encountered these atrocities in northern Uganda in 2003 when we met a boy named Jacob who feared for his life and a woman named Jolly who had a vision for a better future. Together, we promised Jacob that we would do whatever we could to stop Joseph Kony and the LRA. Invisible Children was founded in 2004 to fulfill that promise.” – From Kony 2012 Hompage

Now, six years later, ‚Invisible Children‘ has certainly managed to make Joseph Kony famous. They have also have kicked loose a discussion on Internet activism (or clicktivism) that questions the very claim that sharing a video on Facebook can be a political act in itself.

Now, six years later, ‚Invisible Children‘ has certainly managed to make Joseph Kony famous. They have also have kicked loose a discussion on Internet activism (or clicktivism) that questions the very claim that sharing a video on Facebook can be a political act in itself.

So, to recap- what happened was this (the Guardian has a great timeline online for those of you who’d like it all in more detail):

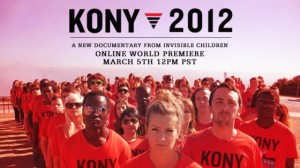

In March 2012 Invisible Children launched a 30 minute Youtube video about the situation in Uganda. Well – more or less. Like some critics have pointed out, the video is actually more about a little white American boy who is really, really sad about the situation in Uganda. The video went viral and has gathered close to 93m views on Youtube so far. (more on how exactly that happened here). Invisible Children has some very practical ideas on how viewers can help stop Joseph Kony.

Their homepage urges users to either

- come to one of the marches,

- to ‚change history‘ by donating money,

- to ‚change the game‘ by messaging one of 12 people Invisible Children have identified as having ’serious power‘ to stop Joseph Kony. All you have to do to make a difference is click on one of the pictures to be supplied with a ready made tweet of facebook status update to post (e.g. @Number10gov Please make it a priority to help stop Joseph Kony and the #LRA this year #KONY2012 )

- or to purchase an ‚action kit‘ to ‚wage war against apathy‘ with t-shirts, posters and bumper stickers. (see picture in the left.) Interestingly the kit does not include any actual information about the political situation in Uganda and about those involved.

Invisible Children’s ’shiny happy people activism‘ gathered traction fast. Soon, however it also faced a massive backlash. The video itself was criticised for oversimplifying the situation in Uganda, for portraying a racist, stereotypical version of Africa and Africans. (also here and here)

The organisation ‚Invisible Children‘ itself came under attack too. Turns out, only a third of the money donated actually made it to Uganda. (I know there is more there but I just can’t get myself to care.)

Dinaw Mengestu from the magazine ‚Warscapes‘ summes up the problematic message of Kony 2012 like this:

Kony 2012 is the most successful example of the recent “activist” movement to have taken hold of celebrities and college students across America. This movement believes devoutly in fame and information, and in our unequivocal power to affect change as citizens of a privileged world. Our privilege is the both the source of power and the origin of our burden – a burden which, in fact, on closer scrutiny, isn’t really a burden at all, but an occasion to celebrate our power. Mac owners can help end the conflict in eastern Congo by petitioning Apple; helping to end the war in Darfur is as simple as adding a toolbar to your browser. The intricate politics of African nations and conflicts are reduced to a few simple boilerplate propositions whose real aim isn’t awareness, but the gratifying world-changing solution lying at the end of our thirty-minute journey into enlightenment.

In the world of Kony 2012, Joseph Kony has evaded arrest for one dominant reason: Those of us living in the western world haven’t known about him, and because we haven’t known about him, no one has been able to stop him. The film is more than just an explanation of the problem; it’s the answer as well. It’s a beautiful equation that can only work so long as we believe that nothing in the world happens unless we know about it, and that once we do know about it, however poorly informed and ignorant we may be, every action we take is good, and more importantly, “makes a difference.” In the case of Kony 2012, this isn’t simply a matter of making a complicated narrative easier to understand, but rather it’s a distortion, or at worse, a self-serving omission of the extensive efforts made over the past decade by the UN, US, Ugandan and South Sudanese governments, and numerous religious and civil organizations across Uganda, to bring Kony to justice.

After the Internet briefly exploded with talk about Kony 2012 the issue disappeared from the (Western) public consciousness just as quickly and is now all but forgotten.

After the Internet briefly exploded with talk about Kony 2012 the issue disappeared from the (Western) public consciousness just as quickly and is now all but forgotten.

So the question is, what happened? Did the campaign, with all its faults, still manage to do some good? Or were those critics right who said is was going to be more bad than good?

There are several articles answering this question. The Guardian has started an open thread on the topic on the topic that is worth looking through.

Rick Cohen from Nonprofit Quarterly argues that Invisible Children’s main success were fundraising and marketing, while it has done little to actually stop Joseph Kony.

If the Kony 2012 video (seen by 85 million people on YouTube and 17.5 million on Vimeo) was to make Joseph Kony famous, it succeeded, but the result hasn’t stopped Kony’s run. In response to the publicity, President Obama (who endorsed the video) sent 100 Special Forces members to Uganda to track the LRA. During a visit with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni last month, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton hinted at the use of drones to flush Kony out from his jungle coverage. However, Secretary Clinton was in Uganda primarily to get Uganda and Rwanda to stop aid (which they denied they were providing) to the Tutsi-led M23 insurgents that are fighting against the Congolese troops of President Joseph Kabila.

As horrendous as Kony is—and he is a version of humanity that is hard to contemplate, prone to recruiting children as soldiers, raping women and girls, and mutilating opponents—Kony has been a minor character in the region for some time even before the Kony 2012 video, and as Clinton’s realpolitik visit showed, Kony is not considered a high priority. By most press accounts, Clinton chuckled when she talked about supplying drones to hunt Kony.

I doubt the fact that Kony 2012 has not made things better for the people of Uganda is a big surprise for anyone. Looking at the Guardian open thread it is nevertheless interesting to see how the Internet can act as a platform for not only campaigns but also for public discussion and public criticism.